|

|

|

|

As Reported by Tony Kay

|

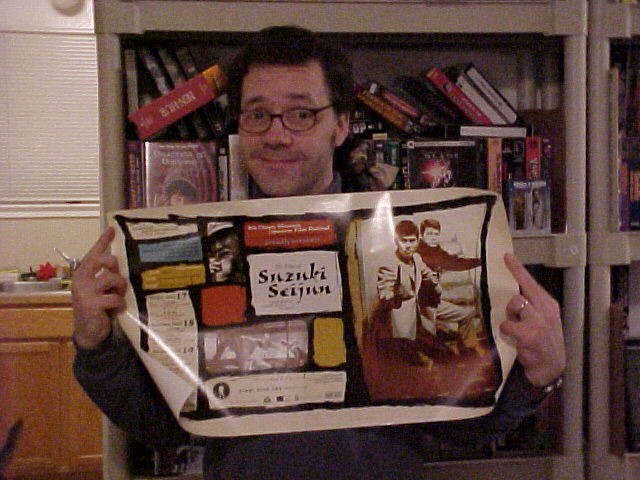

My wife Rita and I first experienced the wild cinema artistry of Seijun Suzuki at the Seattle International Film Festival in 1997. We ventured into a screening of Tokyo Drifter with literally nothing to go on but a sentence or two in the SIFF program guide. Nothing could’ve prepared us for the experience. The neo-film noir saga of former yakuza man Phoenix Tetsu utterly mesmerized us; we were, of course, avowed fans of Japanese cinema from Kurosawa to Godzilla, but Tokyo Drifter was utterly unique, an absolutely mind-blowing amalgam of noir cool, Zen storytelling, and the most eye-popping palate of colors we’d ever seen on a cinema screen. Color us hooked from that point on. We sought out Suzuki’s work, only to find out that it was unavailable through any conventional domestic channels. Finally we tracked down VHS copies of Tokyo Drifter and Suzuki’s art-noir masterwork Branded to Kill via a small mail-order outfit and were able to absorb these gems into every fiber of our being. A year had passed. During a routine workday in April 1998, Rita called me frantically at 3:30pm to tell me that in just two hours, the Seattle Art Museum would be opening a weekend-long retrospective of the films of Seijun Suzuki…and that Suzuki would be in attendance, in person. My boss generously let me scoot out of work early, I picked Rita up, and we were off to the SAM in a proverbial flash. The crowd lined up at SAM was small but enthusiastic, a motley crew of cineastes of various ages and stripes. As we waited in line, Suzuki unobtrusively entered, his translator at his side. He was conservatively dressed in a tweed jacket and dress shirt; his long white hair, goatee, and gentle, unassuming manner lent him an air of serene wisdom more appropriate to a priest than to the father of some of Japan’s most wild-eyed and radical genre films. Once we were seated in the theater, a representative from the Seattle Art Museum gave an introduction, and Suzuki spoke briefly (through his translator), thanking us for our attendance and expounding briefly on the film to be screened, 1958’s Voice Without a Shadow. Simply seeing this obscure gem (never before screened in the Northwest!) was an absolute treat. Voice Without a Shadow weaves a masterful crime story about a Tokyo news reporter’s quest to solve a cluster of seemingly unrelated murders, a classic hard-boiled set-up that deftly weds film-noir toughness with a fascinating glimpse of a Japan in post-war transition. Shot in beautiful, moody black and white, Suzuki contrasts tranquil glimpses of traditional regional life with the seething, sweaty beast of encroaching Westernization. The movie brims with distinctive and striking imagery. One scene in particular—a deceptively languid and gauzily beautiful long shot of a bicycle rider that ends with a gruesome discovery—will forever be etched in my brain. Yet Voice… still maintains the tension and pacing of the best noirs (via some machine-gun editing, decades ahead of it’s time) right up to its white-knuckled conclusion. By the time he shot it, Seijun Suzuki was already (obviously) a bold and assured storyteller with a unique knack for giving American film styles his own cultural and aesthetic stamp. And seeing this formative step towards his explosive ‘60’s style, on a big screen, was priceless. The maestro fielded questions from the audience at the film’s conclusion. Suzuki detailed his affinity for the movie’s source material (a best-selling detective novel by Matsumoto Seicho), and revealed that he was given essentially free rein within budgetary boundaries to adapt the occasionally seamy story; most mainstream American filmmakers of that time should’ve been so lucky! The next film screened, 1963’s Kanto Wanderer, served up a less frenetic (but no less compelling) drama, this time dealing with the day-to-day existence of Kakuta (Akira Kobayashi), a charismatic yakuza in service to the Izu gang. Yatsuharo Yagi’s storyline details a fierce rivalry between the Izus and their sworn enemies, the Yoshida clan, as well as a doomed infatuation that crosses both families. The scarred and tattooed Kakuta’s erstwhile affair with a lady gambler figures into the mix, as does her brother’s status as a Yoshida—an affiliation that leads to violence and chaos. As the film progresses, Suzuki lets fly with loud primary colors and arch stylistic touches, and things get more abstract. Every tiny gesture, every common object takes on grand significance (a decided kabuki influence rears its head throughout). The director punctuates a single decisive swipe of Kakuta’s sword by saturating the scene’s background in sharp crimson lighting. Though statelier in pace than most of Suzuki’s oeuvre, Kanto Wanderer serves up as many rewards as any of the master’s other works. After the second feature, a small table was set up in the lobby, and Seijun Suzuki sat, graciously greeting his fans and conversing with them through his translator despite the rather late hour. He seemed happy, but genuinely perplexed that people on this side of the ocean revered his work so highly. Rita and I pilfered the surroundings for flyers, a program, and some of the lovely SAM posters commemorating the retrospective. Then our turn came. Rita took the opportunity to praise Suzuki for his bold and innovative use of color in his ‘60’s films. “Tokyo Drifter is my favorite movie…” she sighed. Suzuki called her ‘Rita-san’, even writing the moniker in Japanese on the program he was autographing. The director modestly thanked her for enjoying his cinematic ‘coloring book’, and Rita shook his hand, a look of bliss and adulation adrift on her features. As Suzuki interacted so graciously with my wife, my mind raced for something to say when I had a chance to speak to him, the perfect question, or some insightful statement that would launch the man into a lengthy and lively conversation; after all, how often does one get to meet a living legend face-to-face? But my normally chatty nature was utterly undercut by my absolute awe at just being in the man’s presence. In the end, the only thing that I could say, the only sentiment that didn’t seem trite or sappy, was to simply thank him. I leaned toward the young Japanese woman who served as his translator while the director signed my flyer. “Could you please tell Mr. Suzuki, ‘Thank you for sharing your time and talent with us’?” I asked. She nodded and turned to the director, relating my comment to him in his native tongue. Her high, soft voice sounded like a flute playing staccato notes. To this day, I can’t be sure exactly how she translated my simple statement of gratitude (like most slow Americans, I know about six words of Japanese), but upon hearing her, Seijun Suzuki’s eyes suddenly lit up. The look of elation on his countenance took me by complete surprise. A broad smile crossed his weathered face, and he grasped my hand with the force of a man one-third his age. “Arigato!” he repeated several times as we shook hands. I responded with the same word, glowing like a Vegas billboard. Those who know the man’s career know that Seijun Suzuki spent a lot of years creating great movies that were treated by critics in his homeland with relative indifference—and that his fidelity to his muse led to virtual blacklisting in the Japanese film industry for over a decade. The director’s sincere appreciation of everyone in attendance that night was clear and resplendent; in our own small way it felt as if we fans had helped make some of those struggles worth it all for him. Rita and I walked away, waving goodbye to the maestro. He waved back, shouting “Arigato!” once more at us as we made our way out. His reaction was so enthusiastic that it caught the attention of a group of college students near the door. One of them asked, “What did you say to him?” “We just said ‘thanks’,” I said.

|

|

|

|

||

|